This blog is part of our Symposium Spotlight series, where we’re looking back on some of the research that was presented at the 33rd International Symposium on ALS/MND. Today we’re taking a closer look at a talk given in Session 9 focusing on Trial Design and Clinical Endpoints.

Session 9 – Trial Design and Clinical Endpoints, on Day 2 of the Symposium, started with a presentation from Dr Ruben van Eijk from University Medical Centre Utrecht in the Netherlands. His talk, ‘Improving clinical endpoints in therapeutic trials for ALS’ (C24 in the abstracts book) focused on looking at which clinical endpoints should be used in trials for disease modifying treatments. ALS is the most common form of MND and these terms are used interchangeably in this blog.

What is a clinical endpoint?

A clinical endpoint is used to determine if the drug that is being tested in a clinical trial is beneficial to the people it is intended to treat – those effects that directly measure how a participant in the trial feels, functions or survives.

To determine a clinical endpoint, it is important to understand how a person with a disease feels and functions, and this is well understood in MND. So, a drug that improves any of these could be seen to be beneficial.

Whether a clinical endpoint is relevant, and which one should be measured, is driven by the objective of the clinical trial. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) guidelines state that the primary goal of a treatment for MND could be the prevention or delay of disease progression, increased survival and/or improvement of symptoms of MND. They also make a distinction between two types of intervention – disease modifying (for survival and progression) and symptomatic (for improvement of symptoms). Clinical trials for a symptomatic intervention might improve something like muscle strength, which would improve day to day life for someone with MND but is unlikely to make a difference to disease progression or survival.

Both the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the EMA require that if a primary endpoint is an increase in survival, for example, data must also be collected to assess any improvement in function. Likewise, if the primary endpoint is an improvement in function, data must be collected to assess the effect on survival for the drug to be approved.

Current clinical endpoints in MND trials

When considering these endpoints, the options for improving survival are limited, although the definition of survival doesn’t necessarily mean up to the point a person dies. It could be until ventilation is required but that still doesn’t give many endpoints to choose from. However, when it comes to improving function there are many choices and Ruben’s talk now looked at improving clinical endpoints for MND trials that are evaluating disease modifying treatments that focus on function.

There are currently several different clinical endpoints used in clinical trials to assess function. These include ALSFRS-R scores, King’s Clinical Staging and the ALS Severity Scale. Any of these would be considered suitable to use to assess a change in function as a primary endpoint. They all have a common factor – they assess various functional domains (different sets of muscles that control different parts of the body) for example, bulbar function, hand and leg (motor) function and respiratory function. These are assessed using a numerical scale and the score for each domain is then added together to give a total score. This is an easy way to evaluate is a person with MND is declining.

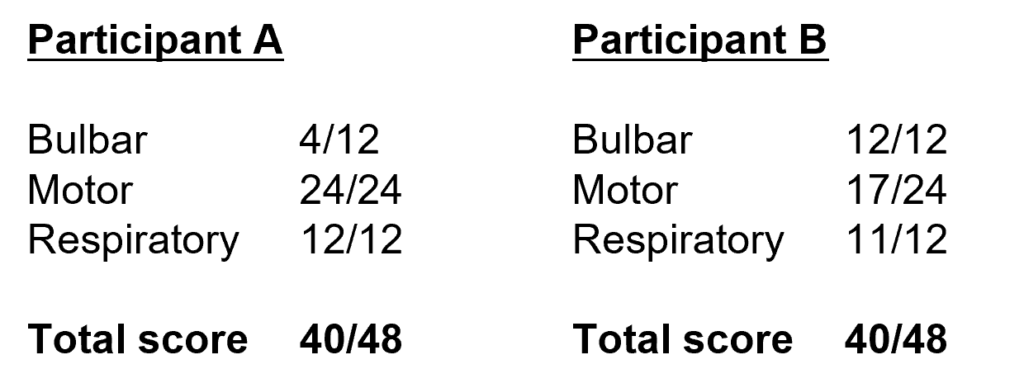

The problem with this system, though, is when the total score is used to compare participants. This is illustrated below:

(Reproduced from Ruben van Eijk’s presentation)

This shows two participants with the same score, even though different parts of their bodies are affected in different ways. Clinically Participant A is likely to have a worse prognosis than Participant B because bulbar involvement generally leads to shorter survival. So, even though these participants have the same score, they actually have a different prognosis, causing variability in clinical endpoints. MND is already a very heterogenous disease, with many factors such as genetics, lifestyle and environment influencing the onset, as well as different survival outcomes and by using the total score the variability between people with the disease increases even more.

This makes it much harder in clinical trials to detect treatment effects – what is related to the treatment and what is down to the random variability between participants? As trials in MND are usually involve quite small groups of participants, groups in which the trial drug is, in fact, having an effect can be missed.

There is also another point to consider. Most people with MND have preserved function in one or more of the domains mentioned earlier. And this is very important when looking at treatment effects. If we have a treatment that effects the total score, whether that treatment effect is relevant really depends on how that person was affected and how it influences each individual domain.

RELATED TOPIC

Blog | 24 November 2021 | Mandy Spencer

Improving clinical trial design – MND Research Blog

How can clinical endpoints in MND be improved?

Ruben suggests that the first step would be to stop trying to assess a disease, with so many different characteristics between individuals, with a single score. Then we can start improving clinical endpoints by refining the assessments for individual domains. He suggests two directions we can move in:

- Improve the assessments themselves for each domain – how well are they predicting clinical events that are relevant?

- How well are they representing how a patient feels and functions in that particular domain?

His vision is that at the end of a clinical trial we have all of these different domains for each individual but we’re not going to look at a total score but at a number of domains. Then we will be able to assess if a drug is beneficial or whether this participant has a worse prognosis compared to others by assessing all of the domains simultaneously. In other words, looking at the totality of the evidence rather than trying to sum it up in a single score.

How can we do this? MND is not the first disease to encounter these sorts of problems and the FDA can provide guidance on how to do trials with multiple endpoints or, in the case of MND, multiple domains and there is a whole array of options, and this is a really active area of research.

One way to tackle this is to simply ask the patient which of those domains they think is the most important and then weight domains according to their preference. We can also ask clinicians and structure it on clinical importance, use predictive models so assess prognostic relevance or we could look at which domain has the most impact on the healthcare budget.

There are many clinical endpoints to capture drug effectiveness in MND and the ones that are most relevant for clinical trials should be aligned with the therapeutic objective of that study. Total scores increase heterogeneity and may not actually reflect how a participant ‘feels, functions and survives’. To improve endpoints we need to start with improving individual domains, and moves are now being made towards this.

With more trials than ever before, and personalised therapies on the horizon, it is good to know that researchers and healthcare professionals are actively seeking the best way to conduct trials that will ensure the best possible outcomes for people living with MND.